Charlie Artingstoll runs mental health projects in Myanmar, including Sin Sar Bar (pictured right), a social change organisation. He graduated in Politics, Psychology and Sociology from King’s College in 2014, and moved to Myanmar thereafter. His speciality is project management and ways in which creative artist advocacy — use of social media influencers, and creative content such as illustrations and animations — can be used to influence and educate people’s opinion on public health issues, in this case mental health.

What are you working on now?

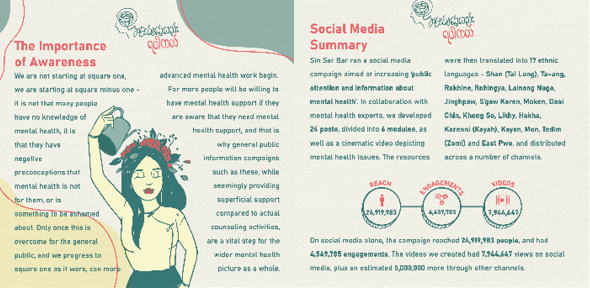

I have just finished a pilot project aiming to address mental health challenges in Myanmar, with a focus on psychosocial support and the lower levels of the MHPSS pyramid of care. We provided trainings for community leaders — teachers, doctors, but also people like shopkeepers — around the country, introducing them to the basic concepts of mental health, and ran a multimedia social media campaign addressing key concepts for basic psychosocial care and emotional well-being. These resources were then translated and distributed into 18 ethnic languages via social media and local community organisations.

I am now developing a proposal with researchers in the CPH network to build and expand on the lessons learnt from the pilot and create a comprehensive systemic response to the situation in Myanmar.

What are the main challenges facing mental health in Myanmar?

It is difficult to overstate how bad the mental health situation in Myanmar is. The current law on mental health is, incredibly, the 1912 Lunacy Act. For years the country had one of the lowest expenditures per capita on healthcare in the world. Furthermore, Myanmar has been in a state of war since the 1940s — the longest running civil war in the world. A slight improvement occurred during five years of democracy but not enough to make up for 60 years of underfunding. There are no post-graduate clinical courses in psychology in the country, and as a result, there are fewer than 10 active clinically trained psychologists in the entire country — for a population of 55 million.

As is often the case with public mental health services, deficiencies in the supply of services go hand in hand with deficiencies in the demand of services — a vicious cycle where a lack of funding leads to a lack of public awareness, which then leads to stigma, misconceptions and low interest in the topic as a whole.

The military coup in February 2021 made what was a dire, albeit improving situation, immeasurably worse. Firstly, the entire public health system was gutted — key ministers were replaced by military appointed officials with questionable expertise and also the civil disobedience movement saw thousands of public health civil servants refuse to work under the new regime. Secondly, the entire population has been exposed to extreme levels of trauma — both first hand trauma — arbitrary arrests, police and army violence — state sponsored terrorism essentially — and second hand trauma — social media in Myanmar has very little in the way of filter or moderation meaning that traumas such as this are often live streamed in grizzly detail.

A study done at the end of last year using the PHQ-9 depression test showed, unsurprisingly, that one in four individuals is experiencing moderately severe to severe depression and in need of psychological interventions.

Another huge challenge comes from the ethnic diversity of the country — between 30 and 40% of the population comes from an ethnic minority, and there are over 135 languages spoken. Many of these ethnic groups face even greater challenges from a public health point of view — funding is non-existent, and exposure to poverty and trauma is often high. Resources, when available, are often only in Burmese which is problematic as many groups see the language as one of the oppressor.

How can these challenges be addressed?

Having spoken to the people I work with, any solution needs to be thorough — both in terms of research and execution — and also systematic — there is much to be done, and few, if any, quick fixes.

We can split interventions into three interconnected spheres: the demand side, the supply side and the institutional. Institutional changes are perhaps the most challenging — working with the current regime is out of the question — so government ministries — which would usually be a cornerstone in projects like these — are out of the picture. Plans can be made for future interventions when the government is replaced and the situation improves, but for now this is off the table. One promising set of institutions however are local community institutions — churches, schools and monasteries.

As a result, we plan on focusing more on the demand and supply side of things. These are interconnected — the same vicious cycle whereby low supply of services leads to low demand in services also works as a virtuous cycle. We think one of the most pressing issues is the lack of availability of higher education in the field, and are hoping to establish a pubic mental health professorship at Chiang Mai University to equip interested individuals with the necessary skills to address mental health issues in Myanmar, ultimately leading to increased regional capacity through a range of academically and professionally qualified public mental health professionals.

On the demand side of things, we will continue to use social media and other unconventional communications channels to get mental health messages across to people via social media and through local community partners. Key to this approach will be having these types of messages available in as many ethnic languages as possible so as to avoid anyone being left behind.

What do you find most exciting?

Having run multiple projects in the field of public health awareness and education, I have noticed that many people aren’t that interested in learning about what you want to teach them.

People use social media to unwind after a long day at work, and for most, spending their downtime being educated on something that either they are unaware of, not interested in, or in the case of mental health — think of as something negative or not for them — is the last thing they want to do. Most of the time people just want to watch cute cat videos, which is understandable.

What is key in situations like this is taking the core message and presenting them as something appealing to engage with (see the below image). While I haven’t managed to get mental health messages into any cute cat videos yet, this could be done in a number of ways: attractive animations or illustrations, having artists or singers open up about their views on a topic, or even through music or short films. Coming up with new strategies in this regard is probably the most exciting part of the project.

What do you find most rewarding?

Though the results of a mental health project like the one we did has quantitative results — ‘Mean happiness’ increased 8.7% and ‘Understanding of factors that contribute to mental health of ones community’ increased by 13.7%— the qualitative responses are by far the most rewarding. If the numbers create a results framework or skeleton, then the participant feedback puts some flesh on the bones:

“... the young people from the IDP camp in Kayah state where I am currently working desperately need this kind of workshop as it's important to address their mental health issues, and it would be extremely beneficial to them. So, I would like to request Sin Sar Bar to deliver more workshops.”

“I feel like I was in a cage before and there is no exit for me. I have a suicidal thought: self-judgment is the only way and I thought it was the exit. I feel useless and wonder if these are just happening to me/why. After taking counseling...I learned that if there is a problem, there is a way to solve it.”