Larysa Zasiekina is a visiting scholar at the Department of Psychology and Director of the Ukrainian Psychotrauma Center. She specialises in studying the psychological impact of genocide in Ukraine and Eastern Europe over generations. Her latest research is centred on gathering stories of war from the initial days of the ongoing conflict between Ukraine and Russia.

Background

Professor Larysa Zasiekina is a clinical psychologist and a leading expert in the areas of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and cultural aspects of memory of trauma. Her focus is on the psychological inter-generational impact of genocide in Ukraine and Eastern Europe, including studies of survivors of the Holocaust and Holodomor and their children.

Larysa Zasiekina has published extensively on language of trauma in high-impact journals in her field and spearheads international partnerships with scholars of genocide in universities of Canada, Israel, US, Switzerland, and the UK.

Zasiekina’s clinical perspective and experience in clinical psycholinguistics are central to her current project “Exposure to Continuous Traumatic Stress (CTS) and Its Consequences among at Risk Adolescents and Young Adults in Ukraine”.

What is your research about?

I work with direct descendants of genocide, such mothers and fathers from eastern/northern parts of Ukraine who are second-generation descendants following the Holodomor - a man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine from 1932-1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. I’ve been researching trauma for 20 years; I started in 1995 just after graduating from university.

I started to collect interviews from living survivors, though now there are no living Holodomor survivors, just their direct descendants. In the Ukraine, a lot of families experienced Holodomor and Holocaust — genocide twice over.

What are you working on now?

I am currently conducting research about trauma about the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war, in particular demographic questions around family trauma. I’m also interested in the effects of political repression. I want to explore collective trauma — could it be manifested now during this war?

Data suggest that some families have higher levels of PTSD, which is more pronounced among people with family history of trauma. I’ve worked with Israeli colleagues to explore this: collective trauma does not manifest during peace times, but in high-risk environments, there is a greater disposition for PTSD.

I’m also interested in something called ‘moral injury,’ which is not a disorder, but involves emotional distress and emotional pain when a person’s moral code is violated, and is pronounced in Ukrainians.

In a recent study, we compared the mental health, and moral injury, of soldiers actively serving during the early stages of the Ukrainian-Russian war with that of civilian students. We found that civilian students had higher levels of moral injury, PTSD, depression, and anxiety, especially females, and that that moral injury predicted PTSD symptoms in both groups.

These findings are important because they could help guide treatment for both soldiers and civilians affected by war.

Where can we find out more about your research?

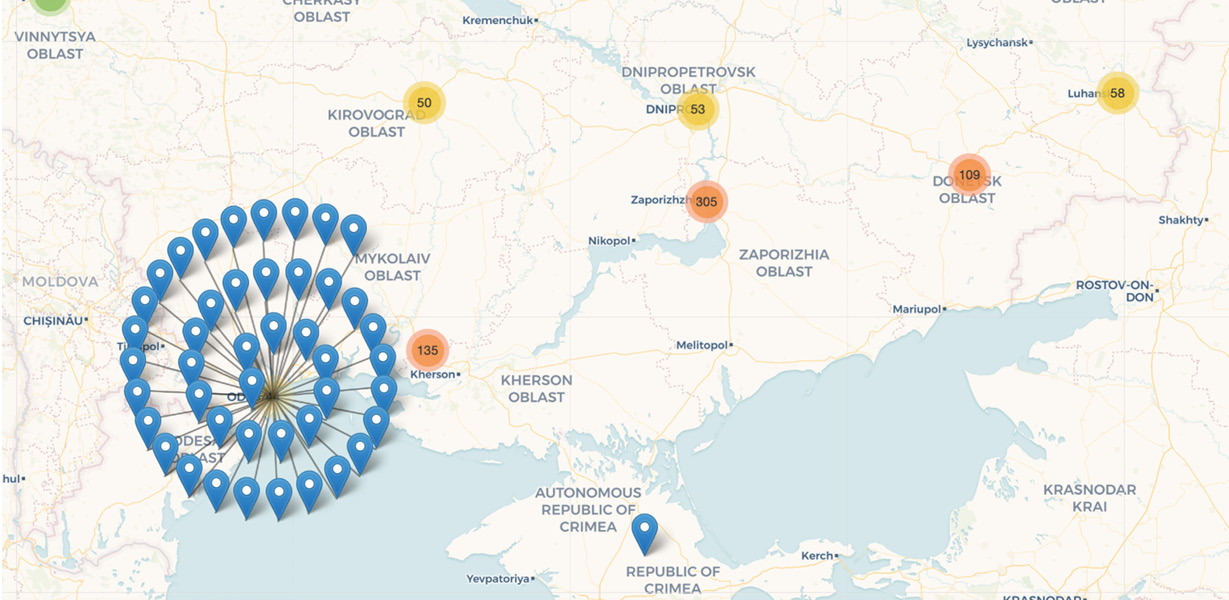

In a new project NoW (Narratives of War) our research team is collecting narratives of the first days of the war in Ukraine. We have an open access virtual exhibition, which compares people’s narratives over time.