By Joyce Coker

May 2025

What does it take to do qualitative research across the Global North and South, not just in theory, but in practice?

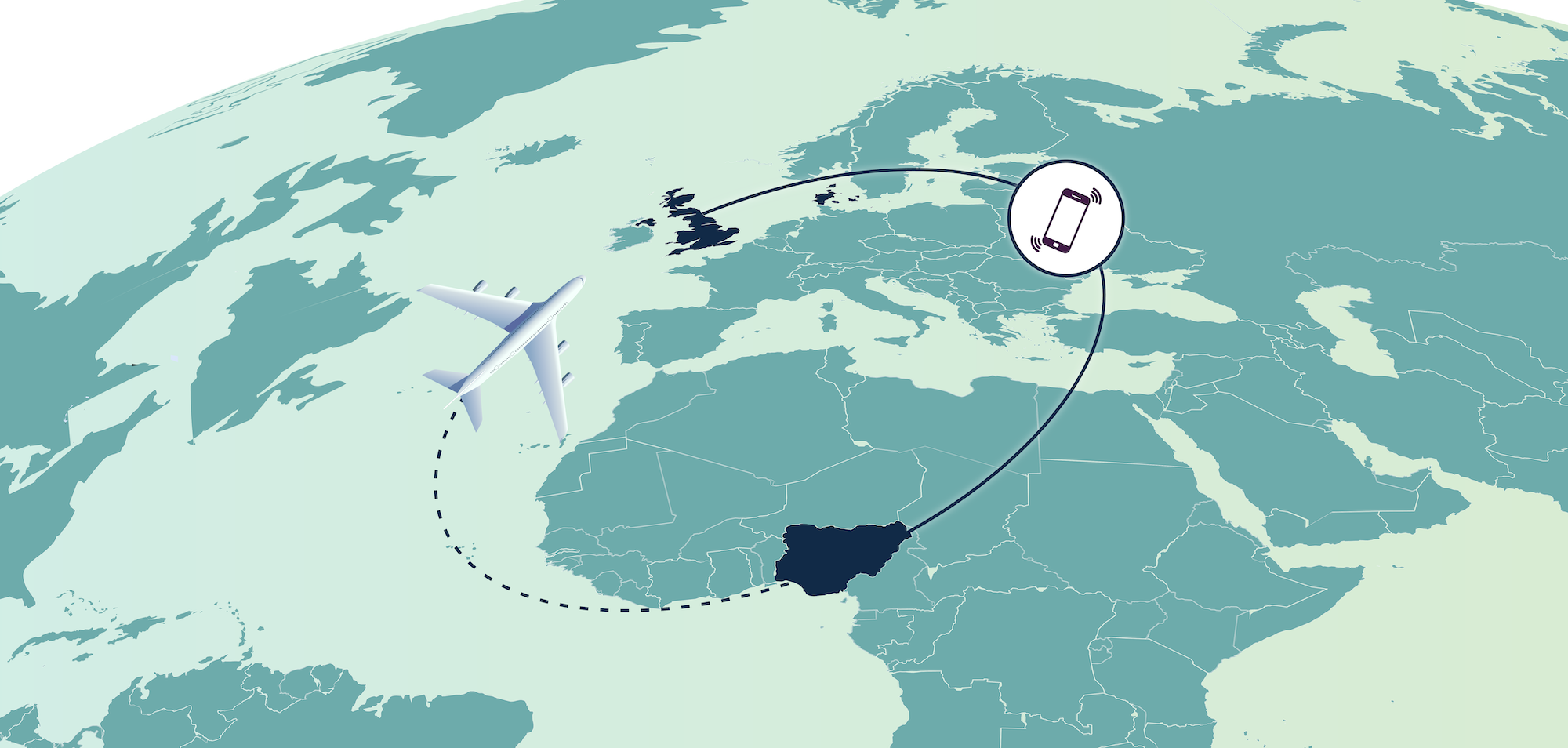

To help fill gaps in the UK’s health workforce, growing numbers of healthcare professionals from the Global South are being recruited into roles across the NHS. This movement supports healthcare delivery in the UK but often puts pressure on health systems in countries of origin, where health workforce shortages are already critical. It also carries personal and social consequences for those who migrate, and for those they leave behind.

One often-overlooked issue is what happens to the ageing parents of healthcare workers who migrate abroad. This becomes especially significant when those adult children are expected to provide care or support, either because it is a social norm and/or because the national policies and care systems to support older adults are inadequate. How is care managed from a distance? And what happens when both sides of the caregiving relationship – parents at home and children overseas – are growing older?

Our recently published chapter, Reflections on Using Digital Methods to Conduct Qualitative Research Between the Global North and the Global South (Springer, 2025), reflects on the process of carrying out a small pilot study in Nigeria exploring these issues. It explores working across countries, using digital methods, and overcoming ethical, practical, and collaborative challenges in a project linking Cambridge (UK), Copenhagen (Denmark), and Calabar (Nigeria). In this blog, we summarise key learning points from the chapter.

Digital methods and inclusion

Our pilot study highlighted both the opportunities and limitations of conducting qualitative research entirely online. The research team used various digital tools, including Zoom, WhatsApp, Skype, and mobile phones, to carry out interviews and maintain communication. These platforms made it possible to work together and reach participants from a distance, but they also shaped who could take part.

Most of the people interviewed were digitally literate and had the resources needed to engage with the research digitally, which may not reflect the experiences of many in Nigeria, particularly those of older adults. This raises important questions about inclusion and the risk of excluding key perspectives when research relies solely on digital technologies.

Adapting methods to the local context

The team’s approach to interview design was informed by discussions between partners, with a focus on making sure materials were suitable for use in the Nigerian context. Interview guides were reviewed and, where necessary, revised to ensure the language was culturally appropriate and would not cause discomfort for participants.

Anonymisation practices were also guided by cultural considerations. While the use of pseudonyms is standard in many qualitative studies, one participant raised concerns about this approach, highlighting the cultural significance and specificity of names in Nigeria. In response, the team chose to use participant numbers, avoiding the imposition of unfamiliar or potentially inappropriate names.

Resource and training disparities

Working across different institutional and national contexts also revealed significant differences in access to research infrastructure and training. Researchers in the Global North had access to academic databases, institutional support for literature reviews, and training in qualitative methods. In contrast, colleagues in Nigeria faced limited access to full-text literature and fewer formal training opportunities in qualitative research.

Despite these differences, the project was shaped by contributions from all partner institutions. During a reflective team discussion, colleagues based in Nigeria described a growing interest in qualitative research methods among local researchers, driven by the need for approaches that can respond meaningfully to local contexts.

Building equitable partnerships

These reflections point to broader structural issues that shape the possibilities for equitable research collaboration. Addressing disparities in access to research infrastructure requires more than ad hoc solutions. Sustainable investment is needed to ensure that researchers in the Global South can access full-text publications and other research resources. Initiatives, such as qualitative research “buddy systems” or train-the-trainer models, offer potential ways to support mutual learning. Embedding qualitative capacity-building within multinational projects can help strengthen participation across contexts. Importantly, increased provision of seed funding is necessary to support the development and sustainability of small- and medium-scale research collaborations between the Global North and the Global South.

Looking ahead

This work is ongoing and continues to evolve. Future research aims to explore care-migration from multiple perspectives. Two MPhil projects are examining how transnational healthcare workers in the UK use digital communication to support wellbeing, and how migration from low- and middle-income countries to Canada intersects with health system resilience amid climate change.

Planned research also aims to expand collaborations in Ghana, offering opportunities to generate both context-specific and transferable insights into how care-migration affects individuals, families, and health systems across borders.